Why ‘growing jobs’ is the wrong objective right now

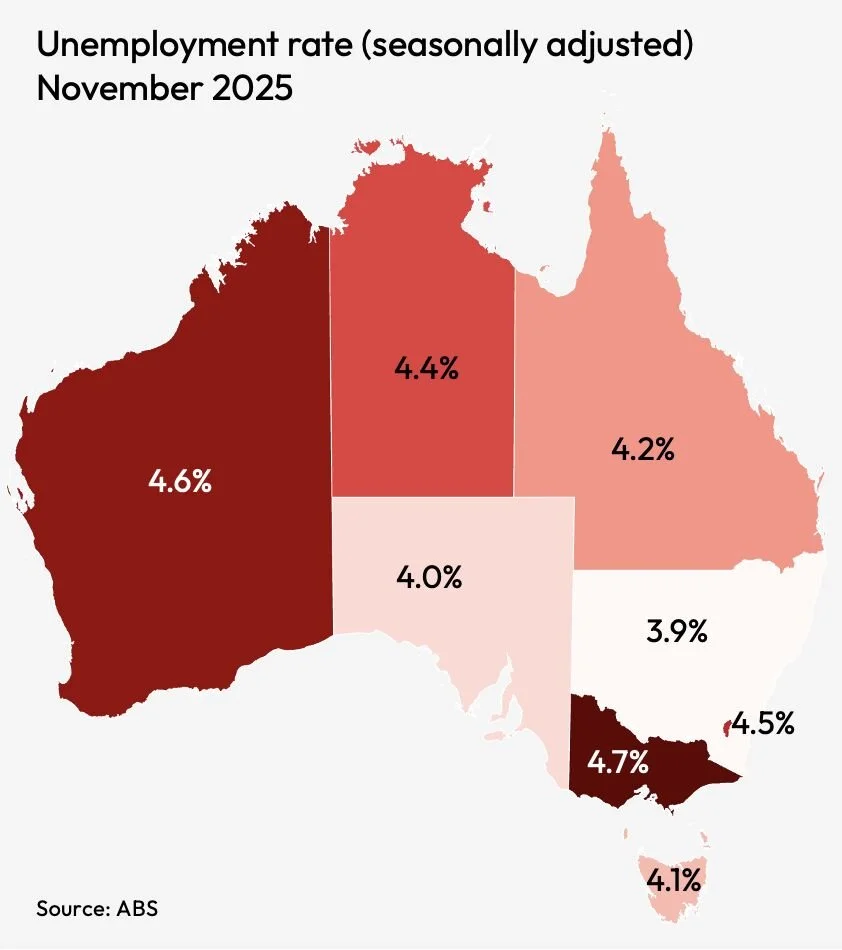

Across most of Australia, labour markets are at or near full employment. Unemployment has edged up, but it remains low by historical standards. In many cities and regions, the binding constraint on growth is not a lack of jobs. It is a lack of workers.

In that context, prioritising job creation often delivers weak outcomes. Adding new roles does little when employers cannot staff the jobs they already have. In practice, it often reshuffles labour between firms or sectors, without lifting overall output, incomes, or resilience.

The more useful frame is economic recomposition: shifting local economies toward higher-value activity.

First, changing the industry mix

In tight labour markets, the composition of the economy matters more than the number of jobs. Shifting toward higher-value industries and roles delivers stronger wages, deeper supply chains, and greater resilience to shocks.

When the unemployment rate is low, every worker used in one activity is unavailable for another. When labour is scarce, supporting low-value or low-productivity activity crowds out higher-value uses of the same workforce. Economic development needs to focus on where limited labour delivers the greatest return. This is why advanced manufacturing, health technologies, clean energy, and knowledge-intensive services matter more than simply expanding lower-value local employment.

Second, lifting productivity

For much of the past decade, economic growth relied heavily on population and workforce growth. That model is now under strain.

Productivity growth has to do more of the work. This includes better use of skills, adoption of technology, improved management practices, and infrastructure that reduces friction. In many places, the productivity gap between firms within the same sector is larger than the gap between sectors.

Economic development can help shape conditions that support diffusion, learning and scale. Without productivity gains, job growth becomes a treadmill. With them, growth becomes more sustainable and less dependent on continually expanding the workforce. Without productivity gains, councils are left chasing growth that depends on more people, more housing pressure and more congestion.

Third, expanding the effective workforce through participation

In a labour-constrained economy, the question is not only how work is organised, but who is able to do it. Even in tight labour markets, too much productive capacity is under-utilised.

Workforce participation varies sharply by age, gender, caring responsibilities, health and location. Under-employment and constrained hours remain common. In many regions, expanding participation is the fastest and least disruptive way to ease labour constraints.

This includes enabling older workers to stay engaged longer, supporting parents through more flexible work structures, improving pathways for migrants to use their skills fully, and reducing barriers for people with health limitations or disabilities.

Participation is not a substitute for recomposition or productivity, but a complement. Higher-value, more productive economies still need people. Participation widens the pool of available labour and improves matching between skills and roles.

There are exceptions. Some regions still face structurally higher unemployment, where job creation remains the right priority. Economic development is always context-specific, and strategy needs to reflect local labour market conditions.

But for most Australian cities and regions right now, success looks different. The relevant questions are whether economic activity is shifting toward higher-value uses, whether output per worker is rising, and whether more people are able to participate productively in the workforce.

In a tight labour market, adding jobs is rarely the binding constraint. The harder task is reshaping the economy so limited labour delivers greater value, supports higher living standards, and builds resilience over time.